John Patrick Shanley's Doubt At Seattle Rep

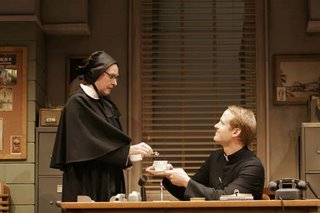

(L-R) Sister Aloysius (Kandis Chappell) shares tea, and suspicions, with Father Flynn (Corey Brill) in Doubt, by John Patrick Shanley. Directed by Warner Shook, scenic design by Michael Ganio, costumes by Frances Kenny, and lighting design by Allen Lee Hughes. On stage at Seattle Repertory Theatre through October 21, 2006. Photos copyright Chris Bennion 2006. Courtesy of Seattle Rep.

Review by Jeremy M. Barker

When the controversy over sexual abuse by Catholic priests reached fever pitch a few years ago (I hesitate to say “broke” because the issue and its extent were well-known if not widely acknowledged before), it was clear that it would receive dramatic treatment. People couldn’t trust their priests anymore, but evidence was so lacking, cases were 20 years old or more, some of the accusers were revealed to be shysters after a piece of lawsuit pie, and in the end the people fitting the bill for bad priests were congregants themselves. Into that void stepped John Patrick Shanley, long a fixture on the American stage but better known as the Academy Award-winning screenwriter of Moonstruck and the writer-director of the beloved but unsuccessful Joe Versus the Volcano.

Doubt, which won the 2005 Pulitzer Prize in drama and opened Sept. 21 at Seattle Rep., takes as its subject not the effect of sexual abuse by priests but rather the gray area that lies between fact and accusation, and its dramatic action somewhat unsurprisingly leads the audience to questions rather than answers.

The play takes place at a Brooklyn parochial school in 1964. The assassination of JFK has punctured the nation’s sense of security, and Vatican II is redefining the relationship between clergy and their parishioners. Sister Aloysius (played with relish by Kandis Chappell), the principal, is an old-school nun with which we are familiar in caricature: she’s gruff, no-nonsense and feared by the pupils. She clamps down on the kinder tendencies of her meek 8th grade teacher Sister James, who wants to relate to her students rather than rule over them.

Enter Father Flynn, a charismatic, Vatican II-style priest (played with a Kennedy-esque air by Corey Brill). He’s bringing a new, human face to the school: he’s engaging, personable, and wants to be more like his congregants--a part of their family, as he comments at one point. And thus the conflict is born: all of Sister Aloysius’s disagreeable qualities ultimately make her a indefatigable protector of her students, while all of Father Flynn’s kindness is cast in a sinister light when the possibility of sexual misconduct arises.

The suspicion comes from events surrounding one of Sister James’s students named Muller. An altar boy, he returns from a private meeting with Father Flynn is a disturbed state with alcohol on his breath. He also happens to be the school’s first and only black student, and later it’s revealed that he’s abused at home by his father for, it is implied, increasingly obvious homosexual tendencies. Thus race and sexuality are added to an already toxic stew of suspicion.

The child is the perfect victim: abused, different and an outsider in the school (and although he never accuses the priest himself, he’s also a perfectly unbelievable accuser, as was born out in the real-life court cases of the last few years).

As mentioned above, the play ends on a note of doubt rather than certainty: suspicions seem validated but proof remains elusive. Shanley strives to portray not the impact of abuse on the victim but rather the issue which the public faces in trying to comprehend the issue: who do we believe? It’s a play with a rather startling power to unsettle the audience, but ultimately it begs the question of whether or not it’s too didactic in its attempt to portray only the doubt. In the case of the Sept. 11 attacks, most dramatic interpretations (films, TV miniseries) have opted for an apolitical tone with regard to the attacks: there are bad guys (terrorists) but questions of responsibility and blame amongst Americans are assiduously avoided, and many critics have understandably been offended by attempts to portray an inherently political moment as devoid of politics.

Much the same criticism could be made of Doubt, which doesn’t directly address the question of blame for actual events. Did Sister Aloysius ultimately go far enough in trying to stop Father Flynn? We don’t know if Father Flynn is actually guilty, which allows for Sister Aloysius to be deeply troubled by her mixed-success at the end of the play; but particularly in the case of a historical piece, we have forty years’ perspective on the issue, and it’s fair to point out that by and large history has not judged people like Sister Aloysius kindly, since guilty priests continued on and were allowed to do more harm. Doubting is ultimately only one side of the story; the other is the record of actual victims, the impact on their lives, the lost promise, the private shame and ultimately public spectacle. Certainty also has a place in this story, but at least we must give Mr. Shanley the credit for having made clear the challenge people faced in grappling with such painful uncertainties, even if it leaves us ultimately wishing to at least partially reconcile our doubt with the painful clarity we now have on this issue.

“Doubt” plays at Seattle Repertory Theater Sept. 21 through Oct. 21. For more information and tickets, visit www.seattlerep.org.

This reviews appears in the September issue of The Seattle Sinner.

Labels: Doubt, John Patrick Shanley, Seattle, Seattle Rep, Theater