And We Thought We Hated the French...

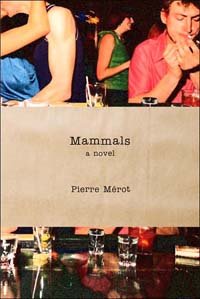

Mammals: a novel

Mammals: a novelPierre Merot

Black Cat, $13

By Jeremy M. Barker

These days, there's only one social novel being written in the Western world. It goes something like this: begin with the assertion the Western culture is decadent, morally bankrupt and perverse; since the Cold War, freedom has been replaced with consumer choice; people lead affectless and unfulfilling lives. Therefore, they revolt, asserting in proper Nietzschean fashion a perversion of their own on the grounds that a perversion of a perversity must be a good thing. Except, in the end, they realize that in the process they've been corrupted by the very thing they oppose, and insert nihilistic or anachronistic sentiment for denouement.

Seriously, that's it. In America, that's Don Delillo, Jonathan Franzen, Chuck Palahniuk; in Canada, the more mild-mannered Douglas Coupland; in Britain, Irvine Welsh; in Italy, Enrico Brizzi; in Poland, Dorota Maslowska; and in France, Michel Houellebecq and now, for the first time in English, Pierre Merot.

What's fascinating is that in America, the perverse rebellion tends to center on violence, whereas in France, it tends to be sexual. In Chuck Palahniuk's Fight Club, the main character starts a fight club for men to act our their socially repressed aggression, which eventually morphs into a terror organization bent on destroying the totalitarian forces of modern society only to, at the end, reveal that the narrator himself is delusionally paranoid and projecting his own anxieties on the world around him. (The crucial failing of the film was that it utterly missed this point, sufficing for taking a cheap shot at the finance industry, as though credit cards were our new field overseers and thus making the entire Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde aspect of the story superfluous.) Michel Houellebecq, on the other hand, revels in sexual perversion: sex as liberation, sex as cheap thrill, sex as economic engine. He loathes everything and his novels are about as spiteful as any imaginable.

It's inevitable that every critic compares Merot with Houellebecq, though in many ways they couldn't be more different. True, the narrator of Merot's novel Mammals, known only as "the Uncle," hates everything: the spirit of the Sixties, capitalism, nationalism, socialism, the welfare state, globalism, women and men. (Thankfully Merot stops short of Houellebecq in his loathing of homosexuals and immigrants.) But generally, critics come out in Merot's favor against Houellebecq, citing the fact that Merot's writing is actually funny. For my taste, most critics take Houellebecq too seriously, not recognizing that he's a satirist working in broad strokes. But it's true: Merot's much funnier in the reading.

The Uncle is a forty-something Parisian, generally speaking a failure in life, love and work. He's the black sheep of his family, though his mother refuses to let him cut the cord. He studied philosophy and therefore has no real skills, though he manages to secure a series of unfulfilling jobs as a journalist, publishing company hack, museum curator and finally teacher. His love life, in true French fashion, is a failure despite a series of beautiful women conquered with precious little effort.

The crucial failing of Merot's book, and generally all the novels of the genre as identified above, is that his real concern doesn't seem to be his characters as much as it is his society. True, Merot is a satirist, but like many a satirist who chooses a large target, he gets bogged down in the details. There's simply no way to convey so much information about all the ways our society sucks in a traditional narrative manner, so authors like Merot create characters who both embody society's worst qualities while having the education and erudition to comment upon them. The novels are almost invariably first person narratives, heavy on comment and generality, shaded with distinctive voicing as though to try to hide the fact that the author is more often than not just preaching.

Central to Mammals is the bar, and drinking in the bar, and drinking alcohol, and alcoholism and drunkeness, and really, the book could easily have been called Booze. (Mammals refers to the occasional theme of family and parenting, and how, in the immortal words of Philip Larkin, "They fuck you up, your mum and dad./ They may not mean to, but they do./ They fill you with the faults they had/ and add some extra, just for you.") The first 20 pages of this brief novel are really just a rambling meditation on bars and drinking, which can discourage the average reader. But when the novel finally gets going, Merot manages to hop, skip and jump through his narrator's tale, past his first marriage to a beautiful Polish red head desperate to live in the West after the fall of the wall, through unemployment and debauchery (best scene is when the narrator's anally fucking a woman in his parents' bathroom during Sunday brunch as she screams obscenities at his mother), through unsatisfying jobs culminating in his successful tenure as a teacher who simply doesn't care but can brilliantly grasp the bureaucratic concept of looking like you're more effective than you are.

The prose is sprightly and amusing, colored by constant, bitter irony. Take, for example, this bit of exuberant writing: "Thanks to its technological wizardry, the Interrnet caters to even the most specialized sexual tastes...In theory, by refining the search using successive pairs of criteria, it is possible to find the precise image around which your sexuality orbits: a fat, balding crone in chains sucking off a teenage Chechen boy in pink tights who is being fucked up the ass by a Breton spaniel in stockings and suspenders, which is grappling with a hairy Japanese man wearing a gigantic dildo whose ass is gaping from the ministrations of the barrel of an American tank, etc."

If it's hard to see how this passage actually plays some role in advancing a narrative, fear not: in many ways, the entire novel is a series of non sequitors, a series of dark jokes at the worst aspects of our society which, in its totality, adds up to damning treatise against our self-satisfied ways.

Perhaps the most distressing thing about reading France's most exportable novelists is that they really make you not want to go to France. Certainly, there's no gang rapes by African youths on the Metro ignored by apathetic passersby (a minor detail in Houellebecq's Platform) in Merot's novel, but the French come off as a society of depressed, dismal people even more vapid than Americans. But that said, my personal guess is that this entire breed of novel, so prevalent globally in the last 20 years, is on its way out. Not only has it largely exhausted its potential (see above dismissive summary), but the times are a-changing. This genre was largely a response to the vapidity of Western liberal democracy and capitalism in the waning days and the wake of the Cold War; this was the dissenting literature of the euphoric post-Soviet days. Now, democracy is at its weakest and most bereft since the 1930s and headed for a crisis unforeseen and unthinkable back in 1989. Of the G8 nations, the US, Germany, Italy and Britain are all ruled by administrations that only exercise power by the slimmest of electoral margins; France, Japan and Canada are ruled by affectless leaders and whose major political parties are suffering from endemic corruption; and Russia has turned away from democracy under the heavy-handed rule of Vladimir Putin. Meanwhile, the Washington concensus of market liberalization is collapsing throughout Latin America, while the EU, after its historic expansion to include former Soviet bloc nations, is mired is disagreement about its future path and rifts are arising as nationalism rears its ugly head in both East and West.

The threat of Islamic fundamentalism, so hyped in the post-Sept. 11 era, is the paper tiger of the era; a problem and a threat, to be sure, but nothing compared to festering disease at home. This isn't to say we're on the verge of the rise of fascism or anything nearly so alarmist, but rather to suggest that the principles that have guided us for the last 17 years are coming to an end, and the bitter estimation of novelists and thinkers once dismissed as mere cynics is coming to pass. A renewal is in the works one way or another, and the first signs of that renewal--like the first signs of the fin-de-siecle decline--will doubtlessly be seen in our oft neglected global literature.